Sports Illustrated:

On His Way - Adam Deadmarsh

May

12, 1997

Maybe the defending champion Colorado Avalanche, which boasts more stars

than NBC's Thursday-night lineup and is deeper than National Public

Radio, does not have it all, but it certainly has more than anybody

else, as Edmonton Oilers general manager Glen Sather suggested last

week even before his team was dusted 5-1 on Friday and 4-1 on Sunday

in the first two games of the Western Conference semifinals at McNichols

Sports Arena.

Consider the Avalanche

lineup. There is Patrick Roy, the most formidable playoff goaltender

in history, who has, through Sunday, won more postseason games (92)

than anyone else. There is the scaled-down model of the mid-1980's Wayne

Gretzky-Mark Messier one-two punch in centers Peter Forsberg and Joe

Sakic, who at week's end was the only player to have scored a point

in every one of his playoff games this year. There is the personification

of nails on a blackboard in dastardly right wing Claude Lemieux, who

sandbags for the six-month regular season and then turns into a postseason

monster, with 25 goals in his last 47 playoff games. There is high-octane

defenseman Sandis Ozolinsh, the attacking wizard who is dangerous at

both ends of the ice.

Then there is forward Adam Deadmarsh.

His name might not yet be properly etched in the public's consciousness

or, for that matter, on the Stanley Cup-it was spelled DEADMARCH

until he caught the typo last September and the NHL silversmith was

summoned back to work-but it certainly will be if Colorado repeats.

Fast, bruising Avalanche power forward

Adam Deadmarsh is ready to be a big-time NHL star

Deadmarsh, who turns 22

on May 10, is the Avalanche's overlooked star, a blur of a player who

can beat any goalie and beat up just about anyone else. There are some

nights when Deadmarsh seems stuck in neutral-"When Adam stops moving,"

Colorado coach Marc Crawford says, "so does his brain"-but

usually he doesn't so much skate as hurtle down his wing, crashing the

crease in search of rebounds. In 22 playoff games last spring he had

17 points and established himself as a force. Through the Avalanche's

first eight playoff games this season, Deadmarsh had six points and

countless

bodychecks. "Deader's a tough kid who plays tough," Roy says.

"He's not afraid to go hard to the net, not afraid to go hard at

some guy on the other team, not afraid to fight."

He also is a happy reminder that a Pig can fly.

While Deadmarsh prefers his more prosaic nickname, Deader, he also answers to Pig, a moniker that the trainer of his junior team, the Portland Winter Hawks, hung on him six years ago after he left his sweaty equipment on the dressing room floor. Deadmarsh insists he has cleaned up his act since then, and his girlfriend of seven years, Christa Brown, says Deadmarsh has definite domestic potential. "He does laundry," Brown says, "and I've taught him the proper way to fold towels."

Although towel-folding

won't make Deadmarsh first team all-Martha Stewart, his home-ec skills

have come a long way since his rookie season with the Quebec Nordiques

in 1994-95. Now he can bake an acceptable salmon fillet, a major step

up from two years ago, when his specialty was pasta ala Palmolive. "I

bought a big pot to cook spaghetti as a pregame meal," Deadmarsh

says.

"My mom told me to wash it out before I used it, which makes a

lot of sense."

Apparently, she forgot to tell him that he should also rinse it.

"Gee, I thought he

got the nickname 'Pig' because of how much he eats," says Colorado

right wing Mike Keane, Deadmarsh's road roommate. "Christa says

he doesn't eat much at home, but he makes up for it when he's gone.

That boy eats enough for a small country."

Deadmarsh's physique is

as much a body by Arnold Bakery as by Arnold Schwarzenegger, though

his 200 pounds are well spread out over his nearly six-foot-one frame.

When Deadmarsh was taking college courses in Portland during his junior

hockey career, he passed French but flunked weightlifting because road

trips forced him to miss too many classes. He could conjugate etre,

but he wasn't able to do his classwork on the team bus. "From time

to time Adam's percentage of body fat" - currently 12.6, slightly

above the Colorado

team average - "has been a cause for discussion around here,"

Crawford says. "It's sort of the benchmark."

But the more important benchmarks in the career of the NHL's next top power forward are stars such as Keith Tkachuk of the Phoenix Coyotes and John LeClair of the Philadelphia Flyers. Deadmarsh doesn't have their credentials or their highly developed hockey sense-the ability to get to spots on the ice where the goals can be spooned as easily as custard-but his legs and his fearlessness have put him on the fast track. Tkachuk, 25, didn't have a 50-goal season until his fourth full year, when he was 24, while the late-blooming LeClair, 27, finally had his first 50-goal season in his fifth year, at 26. Deadmarsh led Colorado with 33 goals in '96-97 while moving around like a pea in a shell game.

When Forsberg and Sakic

were injured for long stretches, Deadmarsh moved to center. When Lemieux

went down, Deadmarsh played right wing with Forsberg and Valeri Kamensky.

Mostly Deadmarsh played on Sakic's right side, but when Keith Jones

tore an anterior cruciate ligament against the Chicago Blackhawks in

Game 6 of the opening round, Crawford moved Scott Young to Sakic's line

and shifted Deadmarsh to left wing. "He can play all three forward

positions," Crawford says,

a tight grin telegraphing the punch line, "although some would

say that's because Adam doesn't know where he is on the ice."

Penalty box could be his other position. Deadmarsh, who had two Gordie Howe hat tricks this season-a goal, an assist and a fight--didn't shrink on March 26 in the 148-penalty-minute bloodbath against the Red Wings in Detroit. The Wings were still seething about Lemieux's jawfracturing cheap shot on Kris Draper in the 1996 playoffs, and Colorado was upset over an early season match in Denver in which two Avalanche players were carried off the ice as a result of questionable hits by Detroit players. In the March 26 game, which the Red Wings won 6-5 in overtime, Deadmarsh scored one goal and fought not only Detroit defenseman Vladimir Konstantinov but also the Red Wings' rugged forward Darren McCarty. If armchair fans of Armageddon get their wish for a conference final between Colorado and Detroit, Deadmarsh and his toughness will be center stage no matter which position he plays. Crawford says that even against the Oilers, with their quick forwards, Deadmarsh's speed makes him one of the Avalanche's key players.

Deadmarsh, Colorado's leading goal scorer

this season, also loves it when the going gets rough.

The curious thing is, Deadmarsh almost didn't make the Winter Hawks as a 16-year-old because he was a plodder. He was a fourth-liner who would grind because he couldn't do much else. When he turned 17, however, Deadmarsh got bigger and sprouted wings. Suddenly he was a firstround prospect with a seductive combination of speed, hands and attitude, even though he had failed to put up the Nintendo-type numbers common among junior stars. Deadmarsh never even had a 100-point year. Going into the last game of '93-94, his final season in Portland, Deadmarsh had 96 points, and Tom and Bede Nishimura, the couple with whom he billeted, put two $500 savings bonds under a refrigerator magnet and announced that they were his if he reached the century mark.

"Naturally Adam let it be known in the locker room," says

Bede, who prepared Deadmarsh for interviews by sticking a long wooden

spoon in his face when the two were in the kitchen and asking, What's

the mood in the room tonight? "Lonny Bohonos [now with the Vancouver

Canucks] was one of his linemates, and Lonny told Adam he'd pass him

the puck all game if Adam promised him $250. Adam told him no. Well,

Adam got one point in the first period, one point in the second and

one point in the third with about eight minutes to go. For the last

three minutes, Adam wouldn't get off the ice. The coach was telling

him to get off, but he wouldn't. Everyone wondered what was going on.

When the game was over, he looked up and saluted us with his

stick. It was so sweet."

Despite his abilities, Deadmarsh wasn't invited to try out for the Canadian national junior team in '92. The American program wasn't flush with talent, so Deadmarsh-who grew up 10 minutes from the border, in Fruitvale, B.C., but is a dual citizen because his mother, Eileen, is from Washington state-played for the U.S. in that year's world junior championships. He is now, and surely will be next February in the Nagano Olympics, a red, white and blue star. Last September in the World Cup finals, Deadmarsh scored the last goal in the dramatic 5-2 victory over Canada.

"You know, it was pretty amazing," Deadmarsh says. "I had hardly won anything in my life, then within three months I win the Stanley Cup and the World Cup. Incredible."

Deadmarsh, who had Grateful Deadmarsh T-shirts tossed to him by adoring fans during last spring's Stanley Cup parade, spends much of his time off the ice competing with Forsberg, his best friend on the Avalanche. For mythical championship belts, Deadmarsh and Forsberg will play pool, golf and hoops and even bowl. (Deadmarsh admits to about a 150 average.) They also have matching Harleys. "I like Adam because he's an honest person," Forsberg says. "He's really straight. There's nothing complicated about him. He likes to fish. He likes to hang around."

On the ice Deadmarsh is anything but laid back. Crawford frets over him because he talks himself into slumps, worrying his way through a week of games if he has nothing tangible to show for them on the score sheet. "He's been so important this year, assuming more responsibility when Joe and Peter were injured, matching up against top centers, battling," Crawford says. "He just has to let his talent flow."

"The only thing that matters," Deadmarsh says, digging deep into his stock of wooden-spoon comments, "is if this team wins."

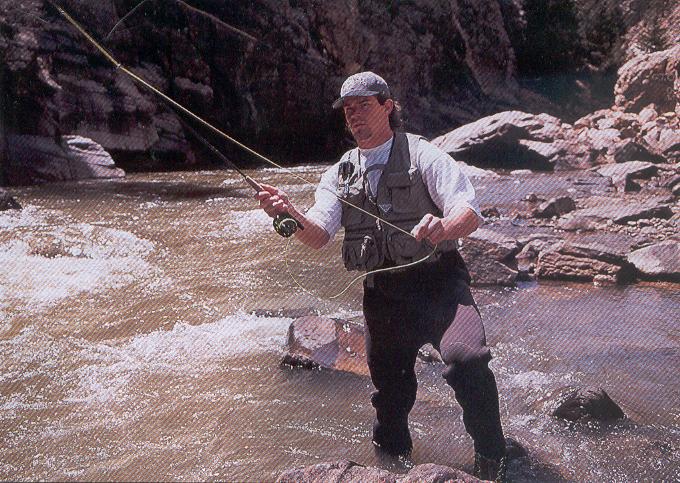

The laid-back Deadmarsh, who's hooked

on bowling, hoops and pool, also enjoys casting about.